Mark Skousen's Contributions To Economics

Following my review of Mark Skousen‘s paper on GDE, I was pleased to discover this piece by Ken Schoolland, Professor of Economics, Hawaii Pacific University, chronicling Mark’s contributions to economics.

“If I have been able to see farther than others, it was because I stood on the shoulders of giants.” — Sir Isaac Newton

Carl Menger, Eugen Böhm-Bawerk, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, Murray N. Rothbard, Roger W. Garrison, and many others have laid the foundation for Austrian economics. One more deserves acknowledgement. Mark Skousen’s scholarship has been highly innovative and ambitious in dethroning and supplanting three principal forces in modern economics: (1) the Keynesian macro model of big government; (2) Paul Samuelson’s popular Economics textbook, which promoted the welfare state, progressive taxation, and an anti-saving mentality; and (3) Robert Heilbroner’s Worldly Philosophers, whose favorite economists are Marx, Veblen, and Keynes. Market-oriented economists have published numerous critiques of Keynesian economics, but the best way to fight a bad idea is by developing a better idea. I see Skousen’s efforts as successful in accomplishing this and as a positive contribution to economics.

Summary

Here is a basic summary of his efforts over the past thirty years, followed by a more detailed explanation: 1. Keynes mutiny: The Structure of Production (1990, 2007) develops a universal four-stage macro model that challenges the Keynesian/monetarist monolith. Better than GDP: As part of this 4-stage model, he introduces a new national income statistic, known as Gross Domestic Expenditures (GDE), that establishes the proper balance between consumption (the “use” economy) and production (the “make” economy), and demonstrates that business investment, not consumer spending, drives the economy (thus, confirming Say’s law over Keynes’s law). 2. Exit Samuelson: Economic Logic (2000, 2010) is an innovative new textbook that integrates powerful Austrian concepts into standard economics textbooks and re-establishes classical economic policy. 3. Move over, Heilbroner: The Making of Modern Economics (2001, 2009), a new history of economics, offers a bold running plot with Adam Smith and his “system of natural liberty” as the heroic figure. In short, Skousen attempted to supplant Keynes, Samuelson and Heilbroner – a triathlon feat in economics. Here are the details.

The Structure of Production (1990, 2007)

Skousen’s first important work is The Structure of Production, published in hardback by New York University Press in 1990, and in paperback with a new introduction in 2007.

Structure is a treatise in macroeconomics and a positive alternative to John Maynard Keynes’sGeneral Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). In the early 1980s Skousen addressed the need for an updated macro model of the economy that challenged the Keynesian/monetarist monolith and did a better job of analyzing economic activity and the business cycle. He was attracted to the Austrian idea, originating with Carl Menger and his intellectual descendants, of a time structure of production involving capital- and labor-using stages of production through time.

With The Structure of Production, Skousen created a generalized four-stage macro model based on the ingenious stages-of-production model Hayek developed in his small book, Prices and Production (1931), known as Hayekian triangles. However, if the Austrian macro model would ever challenge and replace the Keynesian neo-classical model, it required a theoretical approach that needed to be updated, one that would fit historical data and modern macroeconomic statistics. Given that Hayek’s model never went beyond the purely theoretical level, Skousen created a 4-stage model that fit government statistics, such as price indices, inventories, employment, and national input-output data. The generalized four-stage model of the economy is illustrated below:

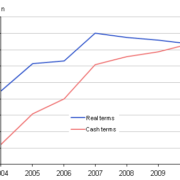

Figure 1. GDE measures spending at all stages of production. GDP measure final output only.

This model fits well into price indices compiled by U. S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). For example, for the “resources” stage there is the raw commodity price index. For the production and distribution stages one could use the producer price index (PPI). And for the retail stage, there is the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Figure 1. GDE measures spending at all stages of production. GDP measure final output only.

This model fits well into price indices compiled by U. S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). For example, for the “resources” stage there is the raw commodity price index. For the production and distribution stages one could use the producer price index (PPI). And for the retail stage, there is the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Aggregate Supply and Demand Vectors

Structure advances the Hayekian stages-of-production model with the introduction of the Aggregate Supply Vector (ASV) and the Aggregate Demand Vector (ADV) as a way of measuring macroeconomic equilibrium, disequilibrium, and the business cycle. Here Skousen notes that the supply chain of production is a downward-sloping schedule that reflects distance and direction over time (thus a “vector”). ASV is determined by productivity, the profit margins at each stage of production, and interest rates. (See Structure, pp. 201-203, and Economic Logic, pp. 583-587.) The payment schedule for goods and services produced at each stage moves in an upward direction, which he calls the Aggregate Demand Vector (ADV). ADV is influenced by time preference, the “natural” rate of interest based on the decision of individuals to consume or save their income. Macroeconomic equilibrium is achieved where ADS = ADV at each stage of production (similar to what Mises called the evenly-rotating economy). When the market rate is artificially reduced to below the natural rate of interest, ADS and ADV move in different directions, and thus create a business cycle. The influence of The Structure of Production can be measured in several ways: as the underground bible for supply-side economics; a revival of Say’s law; an Austrian advance over the Keynesian macroeconomic model and the monetarist disequilibrium model of the business cycle; and a new tool for financial analysis. Its most important function is to serve as a theoretical counterpoint to the standard KeynesianWeltanschauung. What drives the economy? According to Keynesians and Keynes’s law, “demand creates supply.” Consumption drives the production process; consumer spending is paramount, since it represents most economic activity (over 70% of GDP in the US). On the other hand, according to supply-siders and Say’s law, “supply creates demand.” Production drives consumption; saving and investment, technology and productivity, are paramount. Which force is more important?

Gross Domestic Expenditures (GDE)

To answer this question, The Structure of Production introduces a new national income statistic, known as Gross Domestic Expenditures (GDE), which measures spending at all stages of production in the economy. GDE is defined as follows:

GDE = Intermediate Production + GDP

Or in other words,

GDE = “Make” economy + “Use” economy

The creation of GDE is necessary because Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the most common denominator of economic activity, focuses solely on final output, the end product, or what is known as the “use” side of the economy. It ignores to a large degree the “make” side of the production process, the goods-in-process at the intermediate stages of production. As a result, GDP over-emphasizes consumption at the expense of saving and business investment. By adding the intermediate stages, GDE establishes the proper balance between consumption and saving/investment, between the “use” economy and the “make” economy. Drawing from the annual input-output data compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, gross business receipts from the IRS, and other sources, GDE estimates gross spending patterns in intermediate production (goods-in-process) and final output. GDE should be the starting point for measuring aggregate spending in the economy. It complements GDP and can easily be incorporated in standard national income accounting and macroeconomic analysis. In the United States, Skousen’s research shows that GDE appears to be more than twice the size of GDP and he discovered that GDE is historically three times more volatile than GDP. Thus, GDE serves as a better indicator of business cycle activity. (See Skousen’s working paper, “Gross Domestic Expenditures (GDE): The Need for New National Aggregate Statistic,” 2010.) In developing GDE, Skousen behaved in a manner similar to Milton Friedman when Friedman added up components of the money supply to create M1 and M2 in The Monetary History of the United States (Princeton University Press, 1963). Nobody had created the monetary aggregates M1 and M2 until Friedman came along. In Skousen’s case, the IRS provided the raw data — the gross business receipts produced each year from tax returns of corporations, partnerships, sole proprietorships, and farms. By adding them all together, Skousen came up with GDE. GDE is useful in debunking the popular Keynesian myth that consumer spending drives the economy. Granted, consumer spending represents 70% of GDP in the United States, but GDP accounts for “final output” only, and is therefore not fully representative of total spending in the economy. Using GDE, Skousen found that consumption accounts for only approximately 30% of total economic activity, and that business investment (intermediate spending plus final capital investment) is, in fact, the largest sector of the economy. This conclusion is more consistent with the leading economic indicators published by the Conference Board. Again, Say’s law is validated.

Economic Logic (2000, 2010)

Second, Skousen challenged Paul Samuelson and provided an alternative principles textbook to Samuelson’s popular Economics (1948), which forms the Keynesian basis of most modern-day courses in college economics. Establishment textbooks, borrowing from Samuelson, use the perfect competition model in micro and the Aggregate Supply and Demand (AS-AD) model in macro, both of which are defective. Using these models, economists and government officials often support anti-trust legislation, debt financing, excessive consumption, and progressive taxation (all Keynesian mainstays). Skousen wanted to create a principles textbook that removed bad economic theories and replaced them with sound economic principles on a consistent basis. He also wanted to write a textbook was based on his experience as a businessman and investor. Too many economics textbooks are written by ivory-tower academics and are, therefore, too theoretical. Economic Logic (2000, 2010) establishes a logical step-by-step approach to teaching college economics—thus the title. Skousen’s background in business suggested a new pedagogy, beginning the micro chapters with the profit-and-loss income statement, followed by supply and demand. His approach is distinctly Austrian, using Carl Menger’s “theory of the good,” which focuses on the quantity, quality, and variety of goods and services rather than earning income as the best measure of standard of living. Economic Logic begins with the P&L statement (a Austrian-style two-stage micro model), followed by supply and demand analysis. Classroom experience demonstrated that students preferred this innovative approach over the traditional pedagogy of introducing supply and demand first, followed by profit and loss. It is also a good way to introduce economics students to business, finance, and accounting, which are often minimized in economics courses. The macro chapters incorporate Skousen’s 4-stage model of the economy (the first to appear in an economics textbook), and integrate GDE with GDP and standard aggregate statistics, and business-cycle theory. GDE does not replace GDP, it complements it. He also introduced the Aggregate Supply Vector (ASV) and Aggregate Demand Vector (ADV) as a more accurate approach to the business cycle. By integrating “Austrian” elements, his macro model more accurately reflects the dynamics of the global economy, including supply-side technological changes, asset bubbles and commodity inflation, and the boom-bust business cycle. It also reestablishes the virtues of balanced budgets, thrift, and limited government that are absent in Samuelson-style textbooks. Economic Logic also has chapters missing in other textbooks: the origin of money, and the pros and cons of an international gold standard, central banking, and inflation targeting; the Mises/Hayek theory of the business cycle; a full critique of the Keynesian Aggregate Supply and Demand (AS-AD) model; entrepreneurship, financial markets, and government regulation; a review of major schools of economics, including Austrian, Keynesians, Marxist, Chicago, and Public Choice. In sum, Economic Logic does something not previously achieved: It integrates Austrian concepts into the standard economics textbook and has been adopted by a number of schools, such as the University of Detroit-Mercy and Universidad Francisco Marroquin in Guatemala.

The Making of Modern Economics (2001, 2009)

Third, and especially popular with students in my classes on the History of Economic Thought, isThe Making of Modern Economics (2001, 2009). This book reveals a new way to study the lives and ideas of the great economic thinkers. In my estimation, it’s the most fascinating, entertaining and readable history I have seen, and I have encouraged translations abroad. So far it has been translated into Chinese, Turkish, and Spanish. It is a bold history told for the first time as a running plot with a singular heroic figure, Adam Smith and his “system of natural liberty,” at the center of the discipline. Almost all histories of thought have previously been written by socialists, Marxists and Keynesians, with Robert Heilbroner’s classic title, The Worldly Philosophers, being a combination of all three. His three favorite economists are Marx, Veblen, and Keynes. Heilbroner devotes a chapter to Joseph Schumpeter, but only because he is an enfant terrible of the Austrian school. Sadly the sins of omission are too great to salvage Heilbroner. He has virtually nothing to say about J. B. Say, Frederic Bastiat, Ludwig von Mises, Milton Friedman, and, like all other histories of thought, he has no running plot or single heroic figure. On a broader scale, Skousen’s history of economics breaks new ground by rejecting the standard political spectrum, what he calls the “pendulum” approach to identifying economists. In the world of competing ideologies, the standard political spectrum has Adam Smith, advocate of laissez faire, on the extreme right; Karl Marx, the radical socialist on the extreme left; and John Maynard Keynes, supporter of big government, in the middle. This pendulum approach is unsatisfactory since it equates Adam Smith with the extremism of Karl Marx and represents Keynes as the golden mean. In The Making of Modern Economics (and The Big Three in Economics, a shortened version), Skousen presents a unique alternative by creating a “Totem Pole of Economics,” where economists and their theories are measured by their impact on economic freedom and growth. In his ranking, Adam Smith is on top, followed by Keynes, and Marx is “low man” on the Totem Pole of Economics. Thus, the story of modern economics begins with Adam Smith, the heroic figure, and thereafter economists are ranked to the extent that they advanced or retarded Smith’s “system of natural liberty.” Skousen showed how Karl Marx, Thorstein Veblen, John Maynard Keynes, and even some disciples such as Robert Malthus and David Ricardo detracted from the Smithian model of democratic capitalism during periods of economic failure and upheaval, while Carl Menger, Alfred Marshall, Irving Fisher, Ludwig von Mises, and Milton Friedman, among others, remodeled and improved upon Smithian economics as the world economy recovered and prospered. Especially novel, I think, is the contribution of chapter 10, in the middle of the book. It follows the success of the marginalist revolution that advanced the Adam Smith model and established “neo-classical” economics as a formal science. Heilbroner and other historians highlighted the sociology of Thorstein Veblen, a major American critic of “neo-classical” economics without providing a counterweight. Skousen’s middle chapter juxtaposes the ingenious work of Max Weber, the German sociologist who offered a spirited defense of “rational” capitalism. The two sociologists served as a perfect counterbalance. The Making of Modern Economics also breaks new ground by publishing a hundred illustrations, portraits, and photographs, and offering details and little-known anecdotes about the lives and ideas of the economists, including creative chapter titles and musical selections reflecting the spirit of each major thinker. Skousen makes the lives and ideas of the great economists come alive like no other textbook, and my students find it especially refreshing. In sum, I salute Mark Skousen for advancing the theory and history of economics and encourage students and colleagues to study his textbooks and insights.

Books by Mark Skousen

- Economics of a Pure Gold Standard (Foundation for Economic Education, 1988, 1996, 2010).

- The Structure of Production (New York University Press, 1990).

- Economics on Trial (Irwin McGraw Hill, 1991; 2nd edition, 1993). Translated into Japanese.

- Dissent on Keynes, editor (Praeger Publishing, 1992).

- Puzzles and Paradoxes in Economics, co-authored with Kenna C. Taylor (Edward Elgar, 1997). Translated into Korean and Chinese.

- Economic Logic (Capitol Publishers, 2000, 2010). Translated into Chinese and Turkish.

- The Making of Modern Economics (M. E. Sharpe Publishers, 2001, 2009). Now in its 2ndedition; translated into Chinese, Turkish, Mongolian, and Spanish.

- The Power of Economic Thinking (Foundation for Economic Education, 2002). Translated into Chinese.

- Vienna and Chicago: A Tale of Two Schools of Free-Market Economics (Capital Press, 2005). Translated into Chinese.

- The Power of Economic Thinking (Foundation for Economic Education, 2002). Translated into Chinese.

- The Big Three in Economics: Adam Smith, Marx, and Keynes (M. E. Sharpe, 2007).

- EconoPower: How a New Generation of Economists is Transforming the World (Wiley & Sons, 2008). Translated into Chinese, Korean and Portuguese.

About Ken Schoolland

Ken Schoolland is Associate Professor of Economics and Political Science at Hawaii Pacific University, and author of the acclaimed work “The Adventures of Jonathan Gullible.” See http://www.jonathangullible.com/

![image[1]](http://109.104.118.106/~toby/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/image1.png)